1910’s & 1920’s: AIR DEFENCE - THE FORMATIVE YEARS

Members of the Observer Corps during the early period of the Corps

Setting the Scene - The prelude to World War 1

(Source: Ashmore, E.B, Air Defence. 1929)

Germany

A long time prior to World War 1, Germany were making considerable efforts to formulate an airship service for military purposes. As early as 1884, the German army command set up an experimental airship establishment. This was later replaced in 1901 by an airship battalion.

By 1913, the purely military establishment had grown to five battalions, under an headquarters inspectorate. The successes of the German airships grew through the effective use of the Parseval non-rigid and Schütte-Lanz and Zeppelin rigid types of airship. By 1914 they had available a rigid airship designed to carry a useful load of 1,000lbs. of bombs. At mobilisation they could dispose of the respectable total of 232 machines - 34 field flights of 6 machines, 7 fortress flights of 4 each besides parks and some minor formations. .

Great Britain

To these noteworthy preparations we in Great Britain paid little heed. Before August 1914 for instance, the little money that Great Britain could spend on aviation allowed only for flying instruction, and such day work as intercommunication and long-distance reconnaissance. There were neither machines nor ground organisation for night work on any useful scale.

Our flying service had at first been organised as the Royal Flying Corps, divided into naval and military wings. Shortly before the outbreak of World War 1 however there was further cleavage; the wings were more definitely allotted to the two older services, and became the Royal Naval Air Service for the Navy, and the Royal Flying Corps for the Army. Neither service had effective numbers of aircraft to support wartime defensive response.

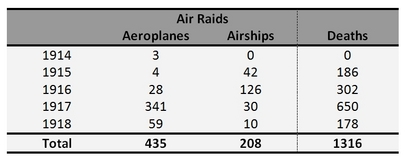

World War 1 - The need for Air Defence

The establishment of an early warning system was initially considered by the Government as early as 1912. At this time however the thought of doing so would create unnecessary alarm amongst the general public. At the lead up to the start of World War 1 (1914 – 1918) however, the need for an air-raid warning system started to become more prevalent. Even though flight at this time was still in its infancy and the overall threat from aerial bombs was not deemed significant as a result, by late 1914 / early 1915, situations changed with the increasing use of Zeppelin Airships by the German Army and Navy to drop aerial bombs onto the United Kingdom.

Although deemed to be an unsuccessful approach, it did stress the need for an effective aerial warning system that provided an indication of the movements of such hostile aircraft - The information being utilised for both defence as well as for air raid warnings.

Following an initial Zeppelin raid on 8th September 1915, the need arose to progress air defences for London. Following this attack, Lord Balfour announced in parliament that the system of defences were to be initially placed under the control of the Admiralty and that Admiral Sir Percy Scott had been appointed to take supreme command of the anti-aircraft defence of London.

Scott; in his memoirs, reflected on this ...

---

"... On 8th September, 1915, a Zeppelin really came over London. Although throughout my career in the Navy I had been specially interested in gunnery matters, I confess that I was surprised when, three days later, I received a letter from Mr. Balfour, who was then at the head of the Admiralty, asking me if I would take over the gunnery defence of London, as a temporary measure, since in due course the War Office would assume control of the work, which, as he pointed out, was really theirs and not the Admiralty's. Mr. Balfour suggested that the task would prove interesting, and reminded me that it was certainly important; but at the same time he warned me, with characteristic kindness, that the means of defence at that time were very inadequate. He was good enough to add that he thought no one was better qualified than I was for the appointment, and he promised that the defences would be improved as fast as the manufacture of new guns and war conditions generally permitted"

"I accepted the appointment, and had a look round the so-called defences. After fourteen months of war they consisted of:

- Eight 3-inch high-angle guns,

- Four 6-pounders, with bad gun sights, and

- Six pom-poms and some Maxims, which would not fire up as high as a Zeppelin, and were consequently only a danger to the population.

The ammunition supplied to the guns was quite unsuitable, and was more dangerous to the people in London than to the Zeppelins above.

In selecting the ammunition to fire at Zeppelins the authorities should have known: first, that a shell with a large bursting charge of a highly explosive nature was required so that it would damage a Zeppelin if it exploded near it; second, that all that went up in the air had to come down again, and that, in order to minimise the danger to the public from falling pieces, an explosive should be used in the shell which would break it up into small fragments. The ammunition supplied was exactly the opposite to what we wanted. The shells had so small a bursting charge that they could do no harm to a Zeppelin, and they returned to earth almost as intact as when they were put into the guns"

Serious as this state of affairs was, it was no reflection upon my predecessor. In getting what he did he had done wonders, for he received the minimum of support, and had to contend against the maximum amount of apathy, red-tapism, and opposition on the part of the authorities. I doubt if many people, in or out of the Admiralty or War Office, really believed, in the early days of the war, in the danger of Zeppelin raids.

But after a considerable interval the citizens of London realized that the German Zeppelins could come and bomb them whenever they liked. On their behalf, the Lord Mayor of London went to the War Office and suggested that they should take some steps to keep the Zeppelins away. The War Office said that they could do nothing. The Lord Mayor then applied to the Admiralty, and their Lordships promised to form an Anti-Aircraft Corps, and supply it with the necessary material to defend London.

The Army, of course, ought to have done their own work, but the military authorities were at the moment overwhelmed with the urgent demands of the Army. The Admiralty took the matter up, because there was no other department to do it, since the War Office was preoccupied. But as the Admiralty decided to undertake it, they should have realised the importance of their task and set about it properly. Had they done so, London, by the end of 1914, could have been defended by at least fifty guns, with serviceable ammunition; instead of which, after fourteen months of war, London was defended by twelve guns firing ammunition which did more harm to the population than to the Zeppelins. Of course, I see the matter in a vacuum, so to speak, and at the time there was an enormous pressure on the Naval authorities, who, after all, were engaged in defending the whole Empire by commanding the sea. London's air defence was a kind of "extra turn."

---

On the 27th November, Scott received a letter from Lord Balfour in which he was notified that the long-drawn negotiations for the transfer of the defence of London against aircraft to the War Office was coming to an end, and with characteristic consideration he proceeded to provide pre-warning that the change was imminent.

At noon on the 16th February, 1916, the War Office took over the gunnery defence of London. Intended primarily to protect London, the system eventually developed into a patchwork of reporting posts including railway stations, lightships and lighthouses, naval shore installations, army camps and police stations, and included a large number of personnel. These personnel generally included the police force's Special Constabulary; but also included railway staff, light ship crews and boy scouts as well as military in the form of army and navy personnel. Many of the spotting stations were not connected whether by telephone or wireless systems and ultimately relied on someone running or cycling to the nearest place that did have a connection. All reports eventually led through to a central administration point (the Admiralty) and then had to be translated into instructions for the most appropriate airfield(s). The instructions were phoned through using the existing public system. Surprisingly the spotting stations were not issued with any equipment with which to take bearings. Nor were they operating and reporting off a set of standard maps.

The process relied upon reporting any aircraft heard or seen within an area of approximately 60 miles of London. Later, this area was extended to include the Isle of White, Hampshire, East Anglia, Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire. At the same time the War Office instructed Chief Constables to forward similar messages to them by telegram. Eventually the system was extended to cover the whole of England and Wales and at the same time reporting lines were structured to reduce duplication of information, so that reports were passed to the Admiralty who would then forward them directly to the War Office. The reliance on the telephone of this system however, still led to significant problems of network congestion. As a result there was growing pressure (and considerable political manoeuvring) for the responsibility of British Air Defence to be turned over to the Army in the form of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). At the time the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army and continued throughout the First World War, until eventually merging with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force.

(The RFC supported the British Army by artillery co-operation and photographic reconnaissance. This work gradually led RFC pilots into aerial battles with German pilots and later in the war included the strafing of enemy infantry and emplacements, the bombing of German military airfields and later the strategic bombing of German industrial and transportation facilities).

This move towards Army control was resisted by the Navy who argued that the defence of Britain against invaders was traditionally a Naval responsibility. Despite some of his comments about British Naval tradition Churchill as 1st Lord of the Admiralty supported them in this. However Churchill resigned in November 1915. The Navy’s performance in air defence in 1915 was less than sparkling and the balance of favour swung towards the Army / RFC and in Feb 1916 the Army assumed overall responsibility for the air defence of Great Britain.

The Formation of the Metropolitan Observation Service (MOS)

One of the first changes to result from this move from Naval to Army control involved the complete reorganisation and rationalisation of the aircraft spotting and reporting system. The "Metropolitan Observation Service" (MOS) was established to replace the somewhat chaotic system of spotting stations; to be replaced with approximately 200 Observation Posts so as to create a more regular system of observers and creating a series of cordons outside vulnerable areas. These posts ringed London at sufficient distance from target areas to allow time for advanced warnings to be acted on. These Observation Posts were all staffed by the police force's special constabulary.

Observation Posts (OP) were simple constructions generally consisting of emplacements surrounded by sand-bags. This reporting system formed the basis of the “Metropolitan Observation Service” for the London area, as this was considered to be the main target area for enemy attacks. The Observation Posts reported to 7 Controls directed by the anti-aircraft defence commanders for particular districts. These would be responsible for declaring alerts in their area, they in turn reported to a coordinating centre, at Horse Guards in Central London. The MOS therefore started to form an embryonic structure from which the Observer Corps later grew.

At the same time the telephone system was improved. The police already had lines to police stations, in which the Police relied upon to pass observations of enemy zeppelins and the Controls had direct access to the trunk system with priority lines being established. The whole system formed the Air Bandit Reporting System (ABRS). The system operating effectively could enable a report of a spotting to reach Horse Guards within 3 minutes. However conditions were not always good and sometimes such a report could take as much as 10 minutes. Moreover the standard of reporting was patchy, incoming aircraft were sometimes missed by posts that should have picked them up, aircraft recognition was poor and the information on bearings and height was on occasions non existent. False reports were not uncommon. Air Defence Area Headquarters had to use a series of disparate reports to try to determine how an attack was developing and what resources should be despatched to counter it. Further improvements were needed.

These took the form of:

- the issue of instruments to all observation posts, these allowed bearings to be taken in both horizontal and vertical planes;

- a standardised reporting format based on common maps and grid system;

- 26 sub control centres to filter reports from posts, this allowed bearings from two or more posts to be used to establish a better idea of position direction and, vey importantly, height;

- the issue of aircraft recognition cards;

- the establishment of a plotting table at Air Defence Area Headquarters, this, the invention of a Major P Fooks, would be familiar to anyone who has seen a WW2 Fighter Command control room. A map covered a large table and symbols representing attackers and defenders were moved on it, using croupiers’ rakes, by women wearing headphones (connected to tellers at the Controls who relayed information as it flowed in). The officer in charge had a seat raised above the table and direct phone lines to all the sub control centres. It took about a minute for a report from an observation post to be reflected on the table.

London Area Defence Area (L.A.D.A)

Early in 1917 however, Germany started to introduce fixed wing aircraft as a more versatile strategic bomber to attack the UK. The Zeppelins only proved to provide a psychological threat and were therefore deemed to be militarily unsuccessful. On the 25th May 1917 a Gotha G.IV bomber dropped its first bomb over Folkestone. The aircraft had proved its worth over the airship leading to decreasing use of the airships in favour of raids by the fixed wing Gotha G.IV / G.V and the aircraft much larger "Riesenflugzeug” (giant aircraft); the Staaken RVI, bomber before Zeppelin airship raids were called off entirely.

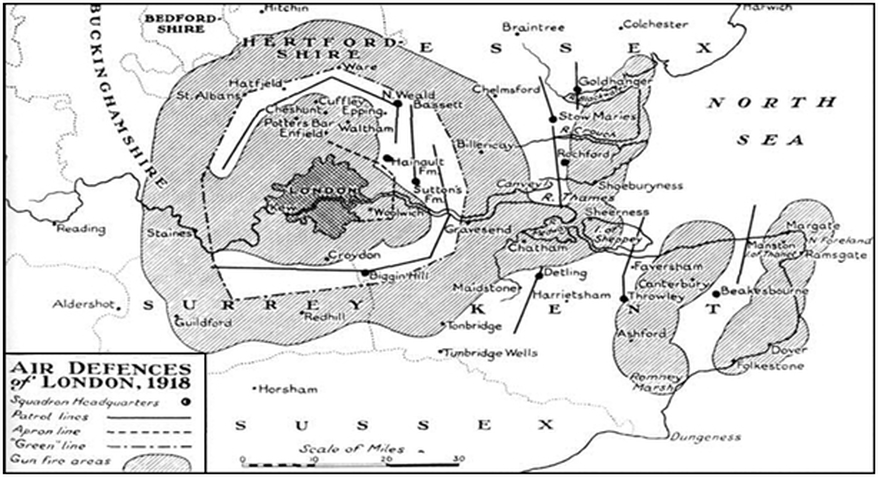

Raids continued in June 1917 mainly on London. But Britain’s air defences were slowly improving and daylight raids were supplemented by night raids to take advantage of the safety of darkness. The main squadron carrying out the raids was called ‘The England Squadron’. The England Squadron Gotha raids continued on 4 July, 7 July and 22 July. Over 120 British aircraft got airborne but only one could find and shoot at the raiders. Again there was public outcry at the failure. The Government reaction, following investigations by the famous South African Lieutenant General (later Field Marshal) Jan Smuts, was to put all sections of ground and air defence of London under the command of one officer. On 31 July 1917, to answer public demands for something to be done. The first of Smuts' recommendations was therefore incorporated with the establishment of the London Air Defence Area (LADA), which covered an area from Southwold to London and then to Rottingdean and aimed to ensure that the anti-aircraft units and nine home defence squadrons of the RFC all cooperated in the protection of London from Aerial attack. This system was further supported by a series of observation posts manned by the Royal Defence Corps and running from Grantham through to Portsmouth.

In charge of this new threat was Brigadier General E B Ashmore who was recalled from his artillery command north of Ypres. and appointed to devise an improved system of detection, communication and control. Major General Ashmore was a trained pilot and had been in command of the 29th artillery division in Belgium. Ashmore officially took command of LADA on the 5th August 1917, with the rank of Major General. Having assessed the system, Ashmore identified that police messages were being received in London in as little time as three minutes; however the average delay was deemed to be greater. He also noted that no reports from an area could not always be taken to mean that there were no bombers in that area. Further to the operation of the system, Ashmore had three overriding concerns;

- A renewed Zeppelin offensive, was relatively unlikely.

- Concern that the Germans would resume daylight attacks on Britain and so his defensive network needed to be effective and fully operational

- A risk of being too successful in dealing with daylight raids by Germany, thereby forcing them to switch towards night-time raids and introducing a whole new range of issues.

The first consideration facing Ashmore, involved the establishment of a protective ring of anti-aircraft batteries around London. 110 guns had been assessed as being required however on 9th August the War Cabinet only authorised the movement of 34 guns, based on the belief that the main priority would be to protect British ports and shipping, and thereby resisting the wholesale movement of anti-aircraft units which would leave the ports vulnerable to attack. The defensive ring formed a 25 mile range from Hyde Park and extending to Ware, Herts in the North and Oxted, Surrey in the South. To avoid anti-aircraft batteries firing on British aircraft, an inner ring was developed. Known as the "Green Line", once the raiders had crossed this line, British fighters could take over from the anti-aircraft guns and given priority to engage attack.

The London Air Defence Area (L.A.D.A) system was fully operational by September 1918 and brought together units comprising coastal and inland observation posts, searchlight and gun stations; balloon aprons, aerodromes and emergency landing grounds into coordinated groups of twos and threes and which were connected to 25 Sub-Controls. Reports from the units were fed through to the centres and then onwards from the centres through to Major General Ashmore’s headquarters. As a result, the system met with some success and although it was not fully working until September 1918 (the last air raid took place on 19th May 1918) the lessons learnt provided valuable grounding for the later development of the Corps.

The peace after World War 1 was followed by a period of strict economy and limited armament. In January 1924, an inquiry was held to investigate the aerial defence of the south east of England, south of a line drawn from Portland Bill to the Wash. As a result of this inquiry it was decided that an organised system was essential for the rapid collection and distribution of information on the movement of hostile and friendly aircraft.

For further information relating to the "First Blitz" please see the PDF file below.

| First Blitz.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1972 kb |

| File Type: | |

Formation of the Observer Corps

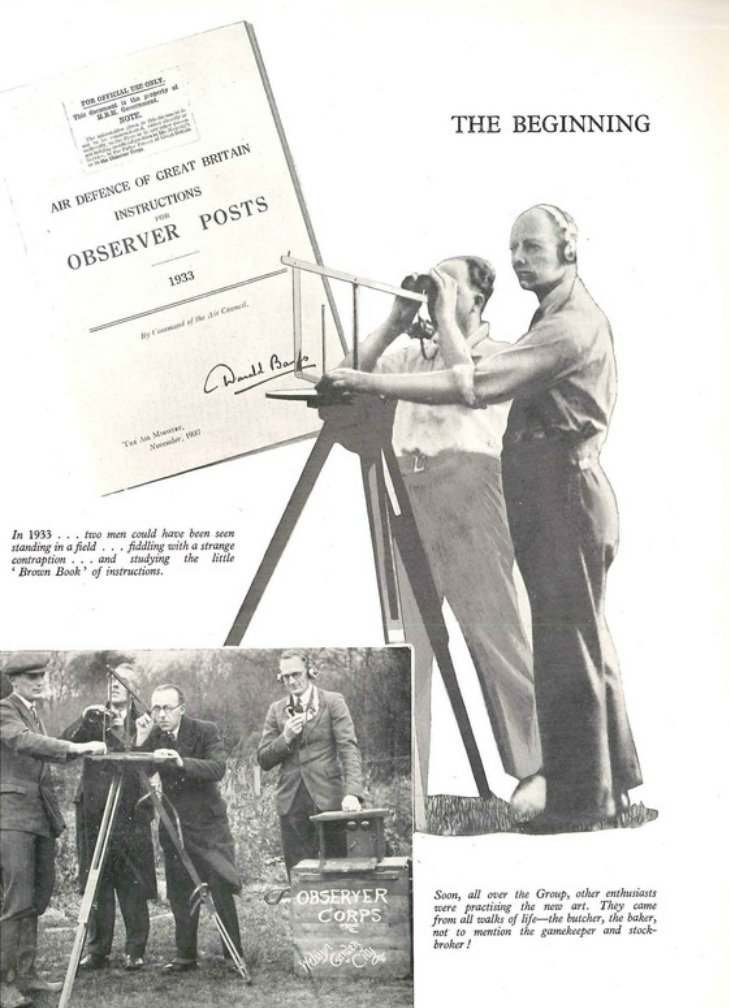

In August and September 1924 the first experiments to assess accurate movements of hostile and friendly aircraft were organised by Major General Ashmore. Using the area of land between the Romney Marshes and Tonbridge, Kent; the following trails proved satisfactory. So much so that, in the following year, two observation areas was formed to cover the whole of Kent, Sussex and part of Surrey.

- No.1 Observer Corps group was based in Maidstone and consisted of 27 posts

- No.2 Observer Corps group was based in Horsham and consisted of 16 posts

With the co-operation of the Chief Constables concerned, these two areas were sited with observation posts and plotting centres manned by personnel who had been enrolled as special constables. After successful observation exercises undertaken during June 1925, the Observer Corps area was extended during June 1926 to incorporate two further groups covering an area from Hampshire through to Essex and part of Suffolk.

- No.3 Observer Corps group, based at Winchester.

- No.18 Observer Corps group, based at Colchester.

Further tests during 1926, proved consistently successful, and plans were therefore made by Major General Ashmore to expand the Observer Groups into Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire. During 1929, control of the Corps was transferred to the Air Ministry with the first commandant appointed to the Corps being Air Commodore E A D Masterman CB CMG CBE AFC RAF (Ret’d). On the 15th May 1931, No. 17 Group, with its centre at Watford, was formed and No. 18 Group was enlarged.

|

|

ROLE OF THE OBSERVER CORPS This film was produced in 1940 by British Pathe, in order to inform the viewer of the role of the Observer Corps in monitoring the skies for enemy aircraft. A role which earned the Corps the title "the eyes and ears of the RAF" |

Image Source: Top - ROCM / Obs Lt John Norman via Buckton, H. Forewarned is Forearmed, 1993

Further text Source -

http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/index.php?/topic/161790-early-warning/

Sutherland, J. & Canwell, D., Battle of Britain 1917, Pen & Sword, 2006

FIFTY YEARS IN THE ROYAL NAVY by ADMIRAL SIR PERCY SCOTT,BT., K.C.B., K.C.V.O., HON. LL.D. CAM

https://www.naval-history.net/WW0Book-Adm_Scott-50YearsinRN.htm